Management of Rotator Cuff Tendinopathy

Evidence for Eccentric Exercise in Rotator Cuff Tendinopathy

The use of eccentric exercise in rehabilitation has increasingly gained attention in the literature recently as a specific training modality for rotator cuff tendinopathy. Histological changes observed in the rotator cuff (specifically the supraspinatus) have been found to have similarities with those of the Achilles and patellar tendinosis (Kahn et al 1999). Furthermore, eccentric exercise has been proposed as an effective conservative treatment in the management of tendinopathy of the Achilles and patellar tendons (Alfredson et al 1998; Murtaugh and Ihm 2013). Therefore, it stands to reason that rotator cuff tendinopathies may also benefit from the advocacy of eccentric exercises.

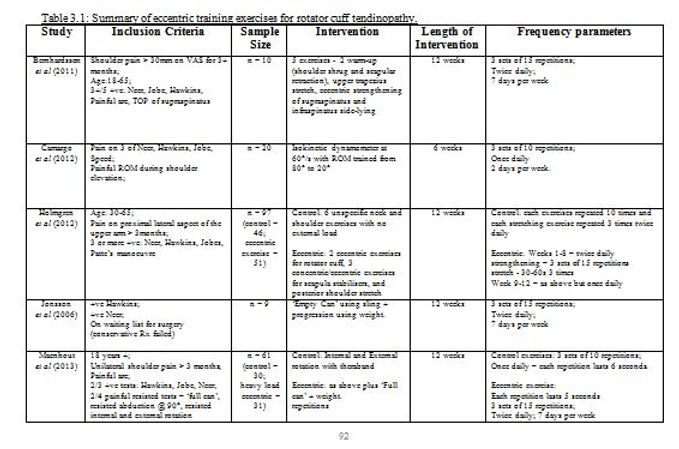

However, very few studies have examined specifically the effect of eccentric exercise alone in rotator cuff tendinopathy and the quality of evidence to support its use is minimal. Those studies which have examined eccentric exercises in rotator cuff tendinopathy are outlined below.

Jonsson et al (2006) conducted a pilot study and showed good clinical results of eccentric training for the supraspinatus and deltoid muscles in chronic painful participants. The subjects had pain for a mean of 41 months and were recruited from a waiting list for surgical treatment. Each participant performed eccentric ‘empty can’ exercises that were allowed to be painful as long as the pain had ceased by the following session. This was completed for the whole 12 week period, and based on Alfredson’s protocol with 3 sets of 15 repetitions being completed twice daily. Once the 3 sets could be completed pain-free, progression of the exercise was achieved through adding weights to reach a new painful training level. After the commencement of the training period, a significant reduction in pain intensity was observed through the visual analogue scale (VAS), and a significant improvement in function was noted as measured by the Constant-Murley score. A 1-year follow-up showed that 5/9 patients were extremely satisfied with their status and withdrew from the waiting list for surgical treatment.

Bernhardsson et al (2011) carried out a similar study examining the effects of a treatment programme focusing on specific eccentric training with progressive loading of the supraspinatus and infraspinatus rotator cuff tendons on pain intensity and function in subjects with shoulder impingement. It differed from Jonsson et al (2006) in that the programme consisted of a greater number of exercises. Overall, there was 5 exercises in the training programme – 2 for warm-up and scapular control (shoulder shrug and scapular retraction), 1 stretching exercise (upper trapezius), while the 2 main exercises were eccentric exercise of the supraspinatus and infraspinatus in side-lying. Interestingly, the frequency parameters used above by Jonsson et al (2006) were also used in this study. This training programme was found to be effective in reducing pain and increasing function. 8/10 subjects had significantly reduced pain intensity levels as measured by the VAS in relation to their baseline score. Intriguingly, the mean VAS change of this study was 30 mm, while Jonsson et al (2006) noted a similar change with a 31 mm difference pre and post the eccentric training. These values are translated into a more clinical context in that previous research has established 14 mm as a minimal clinically important difference (MCID) in patients with rotator cuff disease (Tashjian et al 2009). Function as measured by both the Patient-Specific Functional Scale and the Constant-Murley score was found to have increased significantly in all patients.

Camargo et al (2012) used an isokinetic dynamometer to evaluate and provide an eccentric training programme to the shoulder abductors in patients with shoulder impingement. This was performed at 60°/s and the range of motion (ROM) trained was 60° → 80° to 20°. The training was completed twice per week for 6 weeks with 3 sets of 10 repetitions performed on each training day with a 3 minute rest interval between each set. The Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand (DASH) Questionnaire evaluated functional status and symptoms and was found to have significantly lower values immediately after commencement of the 6 week programme and this was further maintained at follow up 6 weeks later. Practicality issues around this type of exercise arise however as the researchers used an isokinetic device to both evaluate baseline but to also deliver the actual intervention. Problems could potentially arise in incorporating this into a clinical setting.

One obvious limitation from the 3 studies outlined above is that no control group was used in any of the studies. Bernhardsson et al 2011 made an attempt to introduce a control. A single-subject experimental design was used with a baseline period of 3 weeks followed by the 12 week treatment period. As such each subject’s baseline period acted as a control. This is someway improved in that the replication of the design across all the individuals of the study (n=10) enhanced the generalizability of the results. The lack of a clearly identified control group does however prevent the researchers from ruling out the influence of natural recovery on the results, however unlikely it may be due to the chronicity of the subjects included.

However, more recent studies have utilised a randomised control trial (RCT) methodology to examine the effect of eccentric exercises in rotator cuff tendinopathy.

Maenhout et al (2013) examined if there was a superior value to treatment of rotator cuff tendinopathy if heavy load eccentric training was added to conservative treatment. The control group completed the traditional rotator cuff training which consisted of 2 exercises - both internal and external rotation resisted with a theraband. Each exercise was performed only once a day for 3 sets of 10 repetitions. These exercises were performed for a count of 6 seconds, 2 seconds each for the concentric, isometric and eccentric phases of the exercise. Load was increased by changing colour of the band as pain permitted. The exercise group completed the same exercises while also completing the heavy load eccentric exercise which was the eccentric phase of ‘full can’ abduction in the scapular plane with a weight. This was performed at a speed of 5 seconds for 3 sets of 15 repetitions. This was repeated twice daily. Again this was the same frequency parameters used by both Jonsson et al 2006 and Bernhardsson et al 2011. On top of these home exercises, both groups received 9 physiotherapy sessions over the course of the 12 week intervention. The results showed that isometric strength at 90° abduction was the only significant difference between both groups upon completion of the intervention, with the heavy load eccentric group scoring significantly higher over the control group. However, both groups did have equally significant changes for decreased pain and improved function as measured by the Shoulder Pain and Disability Index (SPADI) but the eccentric group was not superior to the control for these outcomes. Subsequently, it can be concluded from this study that there was no significant benefit in adding heavy eccentric loading to a standard theraband -resisted internal and external rotation training programme for subacromial impingement syndrome (Maenhout et al 2013).

This study by Maenhout et al (2013) scored 6/10 on the PEDro scale and failed to score on concealed allocation and failed to blind subjects, therapists and assessors. As a result, performance bias may be relevant as the therapist and investigators expectations may have influenced results

Another RCT was carried out by Holmgren et al (2012) evaluating the effect of 12 weeks of strengthening eccentric exercises of the rotator cuff and concentric or eccentric exercise of the scapula stabilisers on the need for surgery in patients with SAIS. The programme consisted of six different exercises – 2 eccentric exercises for the rotator cuff, 3 concentric/eccentric for the scapular stabilisers and a posterior capsule stretch. See Table 3.1 for details on the frequency parameters. The control group carried out 6 unspecific exercises without an external load and these exercises weren’t progressed or modified throughout the whole rehabilitation period. In addition, both groups received a subacromial corticosteroid injection two weeks before starting the exercise programme and 7 physiotherapy sessions over the 12 weeks.

The exercise group that included the use of eccentric exercises had significantly greater improvement in pain and function, as evaluated by both the Constant-Murley score and DASH, than the control. A significantly lower proportion of patients in the exercise group chose to ultimately undergo surgery – 20% vs 63%.

The results of this RCT are much more favourable than that of Maenhout et al 2012. However, it must be noted that all subjects in both studies did receive physiotherapy treatment concurrently over the 12 weeks making it difficult to fully attribute all the changes in the measures used to that of the exercises. However, the authors make the point that offering a variety of treatments best represent current practice in physiotherapists (Littlewood et al 2012) making their intervention more transferrable and applicable to clinical practice.

Littlewood et al (2013) carried out a review of the systematic reviews which examined the effectiveness of conservative interventions for rotator cuff tendinopathy.

Below are the main findings from each of the conservative treatment which were examined