Rotator Cuff

Shoulder and Rotator Cuff Functional Anatomy

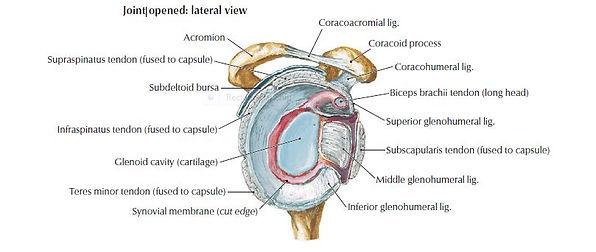

The shoulder complex is comprised of a set of articulations between the upper limb and the trunk. These articulations are the glenohumeral joint, sternoclavicular joint, acromioclavicular joint and the scapulothoracic articulation. Of all the joints, the shoulder has the greatest range of motion (Hermans et al. 2013). The glenohumeral joint involves the articulation between the humeral head and the glenoid fossa of the scapula, and provides the majority of shoulder mobility. As a result of the shallow glenoid fossa the joint relies on static and dynamic stability from the soft tissue structures surrounding it such as the glenohumeral ligaments and rotator cuff musculature (Figure 1.4) (Drake at al 2010).

Fig 1.4: Cross Section of Glenoid Fossa (Hansen et al 2010)

Figure 1.5: Showing rotator cuff muscles and surrounding structures.

The Rotator Cuff is comprised of four distinct muscles: supraspinatus, subscapularis, infraspinatus and teres minor (Figure 1.5). Combined they act as the primary dynamic stabilisers of the glenohumeral joint. In combination they oppose the superior pull of the deltoid muscle (Drake et al 2010).

The subscapularis is a large and flat muscle arising from the infraspinatus fossa on the posterior surface of the scapula. Its primary function is to provide anterior stability of the glenohumeral joint and also assists in internal rotation (Longo et al. 2012). It inserts on the greater tuberosity of the humerus and it is closely associated with the teres minor muscle, arising on the axillary border of the scapula. Both muscles act as external rotators and provide posterior stability to the glenohumeral joint (Figure 1.4).

The supraspinatus muscle arises from the supraspinous fossa of the scapula tracking beneath the coracoacromial arch to insert onto the greater tuberosity. At their points of insertion is it not possible to distinguish the supraspinatus, infraspinatus and teres minor muscles. There is, however, a clear interval evident between supraspinatus and subscapularis. This interval is known as the rotator interval, which is occupied by the long head of the biceps tendon and the coracohumeral ligament (Mochizuki et al. 2009).

Fig 1.6: Diagram showing insertion of supraspinatus (SSP) and infraspinatus (ISP).

Despite common misconception the supraspinatus does not initiate abduction but rather all rotator cuff muscles act in unison to achieve arm elevation (Reed et al. 2013). The stabilizing versus torque producing roles of the rotator cuff is postulated to vary depending on arm position (Tardo et al. 2013). Infraspinatus and subscapularis have the potential to provide a significantly larger contribution in terms of force production, based on physiological cross-sectional area. In contrast the supraspinatus muscle represents only one fifth of the cross sectional area of all the rotator cuff muscles (Mathewson et al. 2014). Length-tension relationships appear to be critical to rotator cuff muscle function. The subscapularis exhibits high passive tension in positions of lateral rotation and abduction, whereas infraspinatus and supraspinatus had maximum passive tension in the neutral shoulder position (Ward et al. 2006). This would indicate that they have a function in stabilising the joint and not solely in force production. The supraspinatus muscle demonstrates structurally different anterior and posterior parts. Each of these parts has superficial, deep and middle sub-regions, with contrasting muscle fibre pennation angles (Kim et al. 2007). In a study of supraspinatus muscle fibre type by Kim et al (2013) the mean percentage of Type I (slow) fibres ranged from 56.73% to 63.97%. Results demonstrated significant variations in fibre type distribution. The middle part of the anterior region has a significantly greater percentage of Type I fibres compared to that of the posterior. The superficial part of the anterior region has a greater percentage of Type II (fast) fibers compared to the middle and deep parts. (Kim et al. 2013). The supraspinatus tendon is comprised of 6-9 independent collagen fascicles. The tendon is capable of compensating for changing joint angles through these structurally independent fascicles and can slide past one another. The tendon attachment exhibits a structure adapted to tensional load dispersion and resistance to compression (Fallon et al. 2002).

The insertion point on the greater tuberosity is covered with fibrocartilage. This fibrocartilage or ‘rotator cable’ is a thickened bundle of fibres that runs transversely across the supraspinatus and infraspinatus tendons. The crescent shaped area of the infraspinatus (See Figure 1.6 starred area) and supraspinatus at their distal attachment is termed the ‘rotator crescent’. This rotator cable has been argued to be vital in the retention of function despite the presence of series pathology or tears (Burkhart et al 1993).

Variations in the vascular supply and structure of the rotator cuff have been well documented (Hegedus 2010). Rothman and Parke (2006) described six arteries primarily responsible for supplying the rotator cuff musculature. The suprascapular, anterior circumflex humeral and posterior circumflex humeral arteries were present in 100% of cases studied. The thoracoacromial, suprahumeral and subscapular arteries were also present in other cases studied. The gross vascular supply of the rotator cuff has been best described by Chansky and Iannotti (1991). In their review of the vascularity of the rotator cuff they concluded that the anterior humeral circumflex artery and the suprascapular artery supply the anterior portion of the rotator cuff while the posterior humeral circumflex artery supplies the posterior portion of the rotator cuff. Although there is some agreement in the gross vascular supply and structure of the rotator cuff 60 years of research has debated the microvascularity. The debate has centred on the presence of a microvascular ‘critical zone’ that leads to tendon pathology. Hegedus (2010) concluded that recent in-vivo studies support the concept of viewing rotator cuff microvascularity on a continuum with no critical zone. This continuum describes an early stage tendinopathy displaying elements of hypovascularity, hyperaemia with partial tearing and again, hypovascularity with full thickness tears. The results the review support the contention that there is some correlation between age, vascularity and rotator cuff degeneration. However, the relationship remains unclear and warrants further investigation.